It was the moment Alex David had been waiting for. He’d paid his dues – and then some – working his way up through Wall Street firms and enduring the humiliation of a failed entrepreneurial venture.

He’d earned advanced degrees, been mentored and mentored in turn, had sold batches of investment vehicles and had won platoons of advisors to firms.

In late 2020, he was at the right place at the right time, the right place being St. Louis and the right time being the chance to reinvigorate Stifel Independent Advisors (then known as Century Securities), a storied but stalled independent advisory brand.

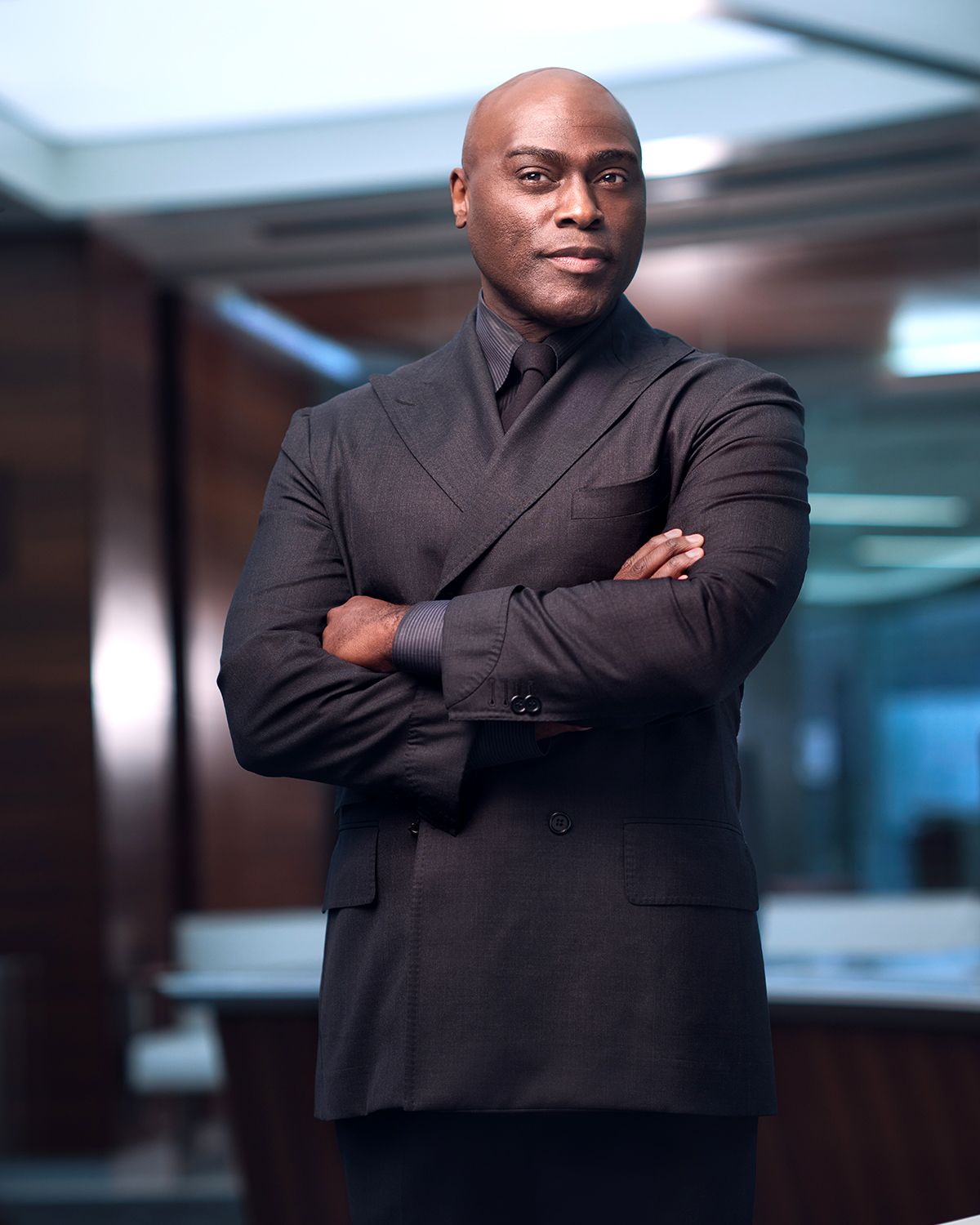

Now, David has stepped onto the national stage as one of the very few Black CEOs in the financial advisory and investment sphere, and as the next generation of leadership at the Association of African American Financial Advisors.

It might seem a tad premature to name David, 52, as the 2023 InvestmentNews Diversity, Equity and Inclusion honoree for Lifetime Achievement, but he has already accomplished what typically takes decades longer. In just the two years since he took the helm at Stifel Independent Advisors, the firm has more than doubled its assets under management to $6 billion and has vaulted to lead diversity in the profession: 40% of newly acquired client assets are overseen by advisors from underrepresented gender and ethnic groups. In 2022, Stifel Independent Advisors drew in 23 new advisors and the $2.53 billion they managed.

And at the Association of African American Financial Advisors, where David took the senior leadership role last year from founder LeCount Davis, corporate donations now are rocketing ahead of prior years, positioning the venerable advocacy group for elevated authority.

A little luck has played into David’s rise, but in large part, he put himself in the right places at the right times. After all, not many New York natives envision that they’ll rise to the C-suite, in Missouri.

“No matter what his lifetime achievement is, he’s just getting started here,” said Ronald J. Kruszewski, chair and CEO of Stifel Financial Corp., who recruited David after a serendipitous dinner meeting arranged by a mutual friend.

BROOKLYN AND BROOKS BROS.

Born May 15, 1970, as the youngest of five siblings, to a single mother in Brooklyn, David recalls running around the neighborhood with friends, doing the things that little boys do: playing pickup basketball, riding his bike and tolerating elementary school.

When he was a young teen, he joined a neighborhood dad’s quarterly, informal Saturday field trips to Wall Street.

“Most of us did not have a father figure. It felt like he had an empathy, a compassion for these young men, to give them something to think about,” said David of the trips to the other side of the East River. “He’d say, ‘that’s where they keep all the money, and that’s the stock exchange. Then we’d have lunch in Chinatown.”

What the adolescent David took from the field trips was exactly what the neighborhood mentor intended: Those cold concrete canyons held just as much opportunity for him as anyone else. Years later, David realized that his Wall Street tour guide was actually a security guard who wore a suit for his commute and changed into a uniform once he arrived at work.

As a teenager and then as a college student in the pre-Internet era, David careened through those same lower Manhattan streets as a bicycle messenger, weaving among men in suits to deliver apparently urgent papers to the doorsteps of firms that did something apparently important.

In high school, a guidance counselor helped him define his aptitudes as a fit for finance, but in college, he pieced together his on-the-fly observations into an initial career plan.

“I had a professor who was African-American, who taught a Saturday class and who worked at Manufacturers Hanover,” he said, referencing the bank that was merged out of independent existence in 1992. “He was explaining the concept of present value and future value and I remember thinking, ‘this is like a new language.’ He was so skillful at not only explaining [concepts] and making it enjoyable and informative and he allowed us to dream. He said, ‘This, too, could be you’.”

David started reading everything he could about financial management, far beyond required texts. And he finally breached a literal Wall Street threshold, gaining a mail room job at an insurance company.

In 1988, a surreptitious scan of the CEO’s copy of the Wall Street Journal, as he rode the freight elevator to the executive offices vaulted him to his second key mentoring relationship.

“I got caught,” said David. “I got caught reading the CEO’s newspaper. By the CEO.”

Instead of scolding him, the CEO invited him into his office and asked the college senior about his career goals and transferred him from the mail room to the accounting department, and then to the bond desk.

His timing was fortuitous. The 1990s were a now-legendary time to cement a career in investing and corporate finance.

At Federated Investors (now Federated Hermes), David gravitated to wholesale sales. “I was buoyed by the whole wave of folks investing and the markets going up. That did help,” he said. “When I saw that I had the ability to influence and coach advisors, that was my sweet spot.” One of his first assignments was to present to a 300-person Merrill Lynch branch office. He saw skepticism turn to intrigue, and intrigue to trust, as the advisors absorbed his ideas, then asked him to speak directly with their high net-worth clients.

He was on the brink of starting a similar job at Lord Abbett when the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, hit. In the uncertain days that followed, Lord Abbett rethought the role that it wanted for David and instead of asking him to keep doing what he had been doing, asked him instead to take on a new, dual role as both an institutional wholesaler and as architect of the firm’s first diversity strategy. The job was a chance to build a new role and department from scratch; a way to directly help communities of color; and assured continued employment – nothing to take for granted in the autumn of 2001.

He took it.

THE STREET AND THE STREETS

At that point in his career, David had dealt with cultural racism at work – the raised eyebrows of colleagues who didn’t automatically attribute to him the credibility that they did to white colleagues. He’d also endured numerous purportedly random stops on the street by police – by 2023, eight in total.

One instance was especially fraught. In 2017, he was driving through Brooklyn to his sister’s house when he spotted his nephew. He pulled over to talk with the young man, who’d just graduated from college with a degree in accounting. As they discussed the merits and downsides of pursuing a master’s in business administration versus a career in public accounting, they were suddenly surrounded by nine plainclothes police officers.

“I was just from a meeting in the financial district and I had a suit on,” David recalled. “They asked us both to get on the ground, and we did, and after they searched us, I told them, ‘I work for Wells Fargo, can I show you my card?’ They accepted that and asked us if we had any weapons. Really? People are selling guns wearing $3,000 suits?”

The next day, continuing to meet with clients, David carried on. A year later, he mentioned the incident to one of the colleagues he’d been working with that week, who was surprised that he could take the stop-and-frisk in stride. “Unfortunately, that’s what Black men go through, whether they’re dressed in a suit or in a hoodie,” David told him. “Sometimes, when people hear about atrocities happening, they assume that the victims are doing something wrong,” he said, referring to the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in 2020. “And sometimes they are, and sometimes they’re just coming from a business meeting.”

ECONOMICS AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP

As it did for millions of other Americans, the economic meltdown of 2008 undermined David’s career momentum. He’d cycled out of the corporate world to earn a Ph.D. in economics and thought he’d make a run at entrepreneurship.

He poured his savings into a couple of New York restaurant start-ups in 2007. The undertow of the 2008 recession was pulling him into ruin when a former client tracked him down and asked him if he was interested in joining Wachovia Bank. Weeks after he started, Wachovia was taken over by Wells Fargo. David managed two regions of financial advisors for Wells Fargo, then two more, and eventually, the entire division, staying at the bank for 13 years.

The opportunity that Kruszewski sketched for David as they became acquainted nearly there ago offered the chance to dust off a moribund brand and fuel its growth by recruiting advisors who feel they’re being overlooked. That strategy has yielded a diversity dividend, as women and ethnically diverse advisors perceive that they will speed their practice growth in ways they couldn’t elsewhere.

The AAAA increased its membership last year by a factor of three and so far this year, corporate financial support is running 30% ahead of last year, said Christian Nwasike chair of the AAAA board and an advisor. Behind the scenes, David has engineered the AAAA’s new role as a go-to resources for Securities and Exchange Commission. One AAAA goal is to double the number of Black financial advisors by 2028, as tallied by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That will happen in no small part, said, Nwasike, through David’s advocacy with CEOs of other financial services firms. “Because he’s a CEO, all his peers are on the bandwagon,” said Nwasike.

“Alex is the person you can ask the questions to help you understand the dynamics outside your personal experience,” said J. Scott Spiker, chair of First Command Financial Services and chair of the Financial Services Institute. “And the fact that he’s now in a CEO position that opens the intimacy among CEOS. We share notes, and his notes are different from my notes.”

David will continue to be pivotal in boosting the AAAA’s stature with the major corporations whose support it needs to achieve its refreshed mission, Spiker said, with a bridge-building approach of shared exploration and shared wins that positions diversity progress as a key business problem that’s essential for all to solve, with shared gains.

Navigating America as a Black man informs and energizes the approach to advocacy David designed at Lord Abbett and has continued at every job since. Daily experiences, he said, help him to appreciate how necessary it is for professionals, especially African American adults, to be a role model and to provide guidance for every young Black male, whether they’re asking for it or not.

“When I’m walking down the street,” David said, “and I see a couple of young Black men, I always acknowledge them: ‘Gentlemen, how are you doing?’ It’s ‘gentlemen,’ always.”

“I think sometimes you see young men going to school, in a store, I think often people see right through them, and the only time they see them is when something bad has happened,” he said. “Acknowledging them is the start. It’s approaching someone with dignity and leaving them with dignity. If all these other things are taken away from me, the one thing I know I’ve contributed is, be kind to yourself and be kind to others. I know I can leave that legacy.”

jcleaver@investmentnews.com